While people may worry about robots taking their jobs, history has shown that the rise of machines is conducive to a rise in employment.

When it comes to robotics, the question on everyone’s lips is, “are robots taking our jobs, and if so, what is left for people?” In 1967, Hermann Kahn wrote a book titled, ‘The Year 2000’, in which he predicted what our lives would be like in 2000.

Even back then, futurologists foresaw that in the year 2000, none of us would have to work, because it would all be done by robots. They said the only thing people would have to think about would be how to entertain themselves. This is not really how things have worked out. However, today there is still talk of robots taking over our jobs. Will this be the case, and should we tackle the issue somehow?

It is true that automation has increased over the years. But conversely, this has also increased employment. In Parliament’s robotics and artificial intelligence working group, my colleagues and I have heard many presentations on this topic.

For example, Maarten Goos, a scientist from Leuven and Utrecht universities, explained that jobs, when we talk about robots, can generally be divided into four categories.

The first two refer to existing jobs. These are current jobs that humans can do, but that machines will do better, and current jobs that humans can’t do, but machines can. The other two categories refer to jobs that only humans will be able to do – at first – and robot tasks that we cannot even begin to imagine yet.

Goos showed graphs demonstrating how, following the industrial revolution, employment grew simultaneously with the rise of mechanisation.

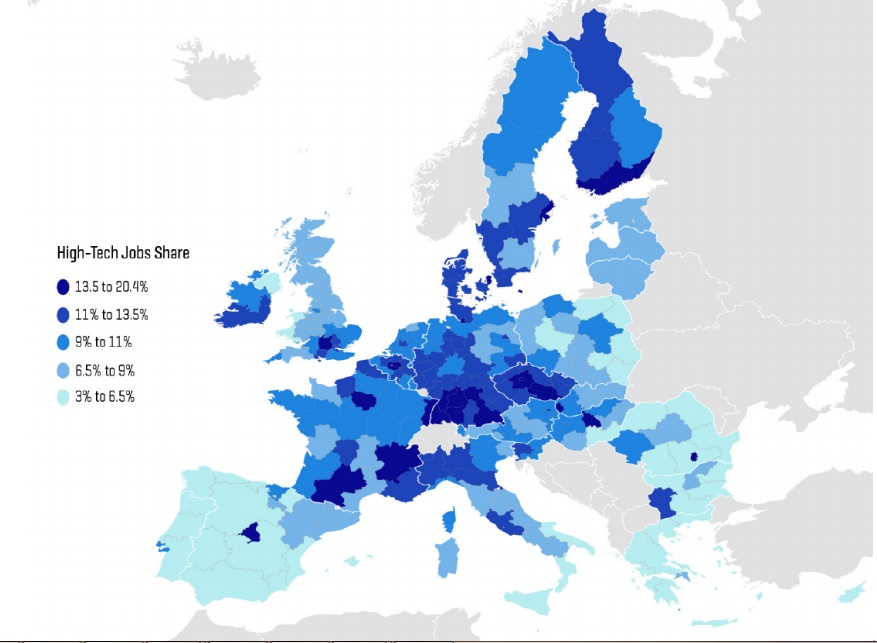

High-tech employment in Europe. Source: Eurostat, EULFS, ONS, UKLFS, Dr. Maarten Goos, data are for 2011

So far, operating a robot or a machine requires someone to have created it, written the software, assembled it and to maintain it. As this categorisation of jobs clearly shows, some jobs that we know today will vanish, but new ones will appear.

It is not true that the rise of robots only threatens low-skilled jobs. Machine learning enables the robots to learn from other machines and the internet. Therefore, robots might also do jobs that require creativity, and that they were not able to deliver before.

But what are the jobs that only humans can do at the moment? They are the jobs that require emotional skills, such as communication and managing people. Writing software for a robot to communicate and understand feelings the way humans do is too complicated.

In answering the question of whether policymakers should do something to avoid robots taking people’s jobs, I am of the opinion that you can’t stop innovation. However, we must be flexible enough to make the necessary changes to allow new jobs for humans to be created.

The article was published in the Parliament Magazine on November 16, 2015